April 14, 2022

Click here for previous Sermon Posts

Recording of the sermon

Sermon

Do This

The Reverend Linda Mackie Griggs

Maundy Thursday

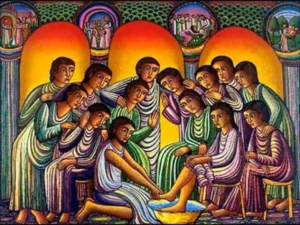

Whether or not we choose to reenact it in liturgy, John’s account of foot washing is what makes the story of the Last Supper whole.

“…This is how you shall eat it: your loins girded, your sandals on your feet, and your staff in your hand; and you shall eat it hurriedly. It is the passover of the Lord.”

For the people of God in Jerusalem that night, it was that time of year—a time of anticipation and preparation. Jesus and his friends are among the crowds gathered in the city for the approaching Passover festival in which Israel’s people remember and celebrate their freedom from Egyptian bondage. The rituals of Passover are rich with symbolism and meaning; they were commanded by the God of creation and liberation in order to remind God’s people of who and whose they are. This isn’t ordinary remembering. This is memory as identity. It is memory as a radical act—a setting-apart of the community in opposition to the powers and principalities of the world.

As the city prepares for Passover, Jesus and his friends feel this opposition more deeply than most. A confrontation is coming between Jesus and the power of the Roman Empire and its collaborators in the Temple hierarchy, and Jesus knows that he will probably not leave Jerusalem alive. But this is the cost of proclaiming a Kingdom far greater than any earthly power. It is the cost of being part of the Dream of God.

And so the friends gather, almost surreptitiously, alert for watching eyes, but unaware that betrayal lurks among them.

What happens next, during their meal together, is only described in John’s Gospel. Imagine the disciples’ consternation as Jesus abruptly gets up, strips to his sleeveless undertunic, ties a towel around his waist and begins to wash everyone’s feet. Imagine the stunned silence, broken only by the gentle splash of water and the rustle of the towel against callused feet. Until Jesus gets to Peter, who cannot keep quiet. To his objections Jesus replies, “Unless I wash you, you have no share with me.” And Peter ultimately relents, as only Peter can, with the zeal of a convert: “…not my feet only, but also my hands and my head!”

The bowl and towel are put away. Jesus puts his cloak back on. “…[I]f I, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another’s feet. For I have set you an example, that you also should do as I have done to you.”

Do this.

Serve one another. Even if it’s uncomfortable.

This is the meaning of Maundy Thursday, from the Latin, “mandatum.” A commandment: Do this.

In John’s Gospel the three chapters following this account comprise what is called Jesus’ “Farewell Discourse,” which boils down to:

“Do this.”

“Serve one another.”

“Love one another.”

These are the words—simple verbs– that change memory into more than memory–that transform memory into identity.

There is more to this story, but it is taken up in Mark, Matthew, and Luke. Jesus takes bread, grown from wheat of the earth, made by human hands. He blesses, breaks, and shares it: “This is my body.” He takes wine, grown from grapes sweetened by thirst, crushed, and aged in darkness. He blesses and shares it: “This is my blood.”

Do this. Remember me.

Bread and wine become Sacrament—a sign of Christ with us, not as distant memory but as active, enlivening presence. When we eat this bread, we say “yes” to the holy in all of God’s Creation. When we drink from this cup, we witness to the suffering of the world.

We are what we eat.

But Eucharist means nothing if we remain at the table. We must go out. We cannot just acknowledge the holy in all of Creation, or just acknowledge the suffering of the world. We must actively witness to both.

We must serve.

We must wash feet.

This is why John’s account of the foot washing is important. Scholars wonder why John focused on this instead of the first Eucharist. Some argue that it distracts from the Eucharist as the main event of Maundy Thursday. But that is only the case if we read the Gospels in isolation from one another. While it is often helpful—and important– to look at them individually in terms of their audience and context, the fact remains that the writers were probably aware of the stories that were being told and written in that time—especially the writers of John’s Gospel, which was written last of the four. But regardless of what was in the mind of the writers at the time, we who have the benefit of seeing all of the Gospels together have the opportunity to let them speak in conversation with one another.

That being said, whether or not we choose to reenact it in liturgy, John’s account of foot washing is what makes the story of the Last Supper whole. It is not a sacrament in the same way the Eucharist is—the water is not blessed, the towels are not fair linen– but it is symbolic of what Eucharist must mean for us if it is to be the radical act of memory that Jesus intended on that poignant night in Jerusalem before his final confrontation with the brutality of Empire.

Jesus had one last chance on that night to impress upon his friends what he had been trying to teach them for three years, so he showed them, through symbol and sacrament, that the Dream of God is about compassion, justice, healing, and forgiveness, and the realization of that Dream will require love, service, love, suffering, and more love. This is not the way of Empire. It flies in the face of earthly power. And that’s the point. In a radical act of memory, it sets followers of Jesus apart in a new identity, in opposition to principalities and powers of the world. It is all about turning the world right-side up by turning it upside-down.

Eat. Drink. Serve.

Don’t just think about it.

Don’t just argue about it.

Don’t even just envision it.

Do this.

Do this, trusting that the God who created and liberated us will continue to do so—liberating us even from the power of death– until the Dream of God is fulfilled. Amen.