April 15, 2022

Click here for previous Sermon Posts

Recording of the sermon

Sermon

The Friday we call Good

The Reverend Mark Sutherland

Good Friday

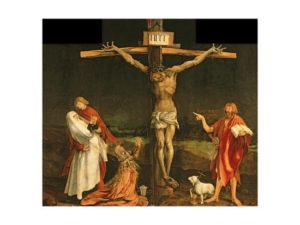

Image: Isenheim Altarpiece- Niclaus Hagenau completed by Matthias Grunewald, 1515 commissioned for the infirmary of a local monastery, where patients could be comforted by message that they were not alone in their suffering

In 2022, Good Friday stands-out in stark contrast against the violence that Vladimir Putin has unleashed upon Ukraine. For me, the connection between the Ukrainian tragedy unfolding before us and Jesus’ death on the cross is so strong that I am impelled to go beyond the traditional pathos of Good Friday.

Today is the Friday we call good. Good does not mean good as we use the word but great as in significant. This day is a day of such significance for Christians that it warrants the name great. Alternatively, there is some evidence that good is a corruption of God as in God Friday. After all we say to one another good day, which can mean have a great day- as Americans now say or a more ancient form of greeting God be with you.

The liturgies of Holy Week and esp. the service simply known as the Solemn Liturgy of Good Friday provide a vehicle – transporting us into the heart of the drama of Jesus last week in Jerusalem. On Good Friday our music is sparse and hauntingly somber as befitting a communal expression of grief and sorrow. Ritual familiarity insulates us in a kind of vicarious dramatic experience. We perform certain rituals and take certain actions dictated by the liturgical protocols of the day as observing participants – watching the action so to speak from the other side of the metaphorical viewing screen – though with livestreaming the screen is often nowadays a literal one. Often the role taken by preachers on Good Friday is to help evoke for the congregation a sense of mood. To encourage those assembled to get into the feelings – to be moved by the pathos of the drama unfolding before us.

Did Jesus feel compelled to journey to his death on the cross? Crucifixion was a form of punishment reserved for political agitators who threatened the fragile stability of the imperial order. Therefore, death by crucifixion was a punishment for a particular kind of treason – thus turning Jesus’ death into a political act.

Did Jesus know how his last week in Jerusalem would end? The gospel narratives depict a degree of intention in Jesus’ decision to journey to Jerusalem. He seems to realize the likelihood of his death there. That he thought he would die by crucifixion is less clear. Nevertheless, his intention was firm because he believed himself to be acting within the drama of God’s dream for the world.

In 2022, Good Friday stands-out in stark contrast against the violence that Vladimir Putin has unleashed upon Ukraine. For me, the connection between the Ukrainian tragedy unfolding before us and Jesus’ death on the cross is so strong that I am impelled to go beyond the traditional pathos of Good Friday.

Tonight, I’m compelled to try to communicate the stark realities of courage in the face of a particular kind of imperial violence. Ukrainians have confronted Putin’s imperial violence with courage. Through the lens of Ukrainian courage we see the stark contours of God’s purpose through the death of Jesus on the cross. Imperial violence is always a form of sacred violence – that is the defense of political, cultural or religious values through violence. By the manner of Jesus’ death on the cross – with all its political significance – God demonstrates the nature of courage in the cosmic confrontation with human sacred violence.

There are two kinds of courage. The first is spontaneous courage – we simply react without time to think in the face of a threat either to ourselves or to others. The second kind of courage is deliberative – we have time to review the situation before deciding to act or not act – we have a choice. Jesus’ journey to the cross is the second kind of courage – deliberative courage. He always had a choice not to do so. Once in Jerusalem he had a choice to shape events towards a different outcome. He made the choices he did because through his deep rapport with God – he understood – if not the manner – certainly the purpose of his death.

So, what was that purpose? In the example of Jesus, God demonstrates for all of humanity the ultimate victory in the cosmic confrontation with sacred violence. In the example of Jesus, God breaks sacred violence’s spiritual and psychological stranglehold over us.

Sacred violence is as old as humanity. It’s so instinctively programmed in us that we cannot imagine any alternative to its cycles of endless repetition. Violence becomes sacred when we come to believe that through it we are protecting God or some other supposed higher principle like national honor. Our propensity to remake God in our own image knows no bounds. Voltaire quipped that in the beginning God created man in God’s own image and ever since humanity has been returning the favor. Caught in sacred violence’s repetitive grip we are blind to the ironic paradox that it’s our sacred violence that killed Jesus – and continues to strike at the heart of God.

Our propensity to remake God in our own image means it is counter intuitive for us to believe in a God whose victory is through dying – even when the ultimate promise is resurrection. To break the instinctive grip of sacred violence upon the human heart – Jesus knew that he – as God’s agent – must first demonstrate the victory that comes only through sacrificial death.

O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, the city that kills the prophets and stones those who are sent to it. The Jerusalem Temple lay at the heart of an anxious and fragile Roman peace. It’s only by going to the heart of empire – that the roots of sacred violence as the ruthless projection of unrestrained power- that God, in Jesus, finally and for all time – breaks its power over us.

The nation of Ukraine – personified to an extraordinary degree in their President, Volodymyr Zelenski , is showing the world the nature of deliberative courage. We are transfixed in the headlights of the Ukraine crisis because for us – on Good Friday in 2022 – their refusal to be turned aside from their moral sense of destiny is showing us what sacrificial walking on the way of the cross looks like.

We all hope and pray that the courage of the Ukrainian people to confront the sacred violence being visited upon them will result in their victory – not despite of but because of the enormous material and human costs. But there is a more important truth. Ukrainian courage and resolve – is a courage that courts a terrible vulnerability – a vulnerability through which they have already won a significant moral victory for humanity whatever the military outcome.

On the cross, God broke the power of sacred violence’s grip on the human heart. Jesus’ death on a cross demonstrates that the repeating cycles of sacred violence are no longer inevitable. The victory of God over death means the choice or refusal of sacred violence is now a matter of deliberative courage. Something to bear in mind as we stand in the shadow of the cross.