April 2, 2023

The Sunday of the Passion

Palm Sunday

Click here for previous Sermon Posts

Weekly Prayer Recording:

The Fickleness of Crowds

The Reverend Mark Sutherland

Recording of the sermon:

Crowds become the conduits for shared cultural and historical storylines. It matters greatly which storylines echo through a particular crowd’s collective awareness. In short crowds can be fickle.We too are the victims of competing storylines. For like the crowds praising Jesus as he entered the Holy City, we enthusiastically hail our next political savior until that is, he or she no longer is. We long to do the brave thing, until that is, the moment when we don’t.

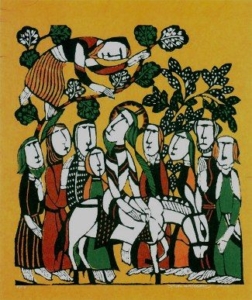

Image: Jesus’ entry to Jerusalem, Sadao Watanabe

There is something mysterious about crowds. Being part of a crowd can be an exhilarating escape from our individual sense of isolation and helplessness. In crowds we find an experience of shared solidarity. An experience of mass protest builds networks to support ongoing action when we return to the sphere individual life. Crowd experiences can become an in-the-moment expression of the more expansive currents of aspiration and longing for change.

But there is also something menacing about crowds. Being caught up in a mass mind-meld can be frightening. Crowds morph in the blink of an eye from peaceful protest to violent action. The journey from exuberant celebration to mass hysteria can be a very short one. We are right to fear being caught up in the experience of mass manipulation when an unscrupulous and skillful orator stokes our fears. Fear-stoked messages become conduits for the surfacing of repressed collective memories and imagined grievances – an experience that we in America are all too familiar with.

Crowds become the conduits for the resurfacing of shared cultural and historical storylines. It matters greatly which storylines echo through a particular crowd’s collective awareness. In short crowds can be fickle.

He had come to celebrate the Passover. Having traveled from Bethany, Jesus entered Jerusalem through the East Gate to the wild acclaim from the crowds that greeted him. They stripped the fronds from the palm trees to lay them as a carpet before him as he entered the city gates.

The surfacing of collective memory – acted out in real time – is often the best interpreter of a crowd’s mind-meld . The waving of palms was a gesture that tells us everything about the mind of the crowd welcoming Jesus.

Jerusalem with its estimated population of 40,000 had swelled to well over 250,000 for the Passover festival. Accommodation in the city was at a premium, hence Jesus, during the two weeks prior to the festival had been commuting the two miles from the Bethany home of his friends Lazarus, Martha, and Mary to the city. During this time his reputation had gone viral. Jesus was the name whispered on every breath. Who is he? they whispered to one another. A question couched within the question – the only question that really mattered to the crowds – is he the one?

It’s the palm branches that tell us everything we need to know about the crowd’s expectations. Like the MAGA – Make America Great Again – slogan – the waving of palm branches was a political gesture echoing and earlier storyline. Some 160 years before, the triumphant Judas Maccabeus, the last leader of a successful Jewish rebellion against foreign domination, had led his victorious partisans into the Temple. One of their first acts of victory was to cleanse and rededicate the Temple – the memory of which is celebrated by the Jewish community in the festival of Hanukkah. For us, the important point is that the partisans used palm branches to cleanse and prepare the sanctuary for rededication after its defilement by the Syrian tyrant, Antiochus Epiphanes, whose erection of a larger-than-life sized statue of himself placed in the Holy of Holies was the initial trigger for the rebellion.

The waving of palm branches speaks of the crowd’s expectations for Jesus as a new national liberator in the mold of Judas Maccabeus – come to free them – this time – from the hated Roman occupation.

Of interest here is to what extent was Jesus the hapless victim of a mistaken historical identity – and to what extent was he deliberately playing into the MIGA Make Israel Great Again storyline – colluding with the crowd’s frenzy of jubilation? Again we don’t need to search far for the answer. Riding into the city on the back of an ass proclaimed another historical storyline – that of the prophet Zechariah:

Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion!

Shout aloud, O daughter of Jerusalem!

Lo, your king comes to you;

triumphant and victorious is he,

humble and riding on an ass,

on a colt the foal of an ass. Zechariah 9:9

Of course, as events played out, we know that Jesus had a very different interpretation of what kingship in this context meant. However, we should not miss the implication here that he seems not to be averse to playing on popular messianic expectation of an earthly liberator king.

At the same time as Jesus entered through the East Gate, another triumphal entry procession wound its way into the city through the West Gate. The Roman Procurator, Pontius Pilate at the head of his Roman Legion had also come up to Jerusalem for the Passover.

Pilate did not live in Jerusalem. He chose to avoid the city’s ancient warrens seething with civil and religious discontent. Pilate and his Roman administration preferred the sea breezes and mod-cons of Herod the Great’s former capital at Caesarea Maritima – 60 miles to the west on the coast and now the administrative center of the Roman occupation of Judea.

Pilate hated and feared the crowds of Jerusalem. He feared them most during the Passover which required him to come up to the city with a show of preemptive force to forestall the potential for insurrection. For Passover celebrated Jewish collective memory of liberation from an earlier period of slavery. Pilate’s arrival was indeed a wise move, for the crowds that hailed Jesus, were in insurrection mood.

Holy Week commemorates the events beginning on Palm Sunday of Jesus’ last week in Jerusalem before the Passover. The echo of three historical storylines emerge from Jewish collective memory to intersect and clash with an alarming result as Pilate, the crowds, and Jesus all become caught up in an escalation of events – which in the end – none could control.

The storyline of worldly oppression and political violence intersects with a storyline of populist resistance and nationalist longing for liberation at whatever cost. Both confront the third storyline which concerns the next installment in the epic narrative of God’s love and vision for the world.

I have spoken over recent weeks and days concerning Holy Week and the Triduum – the Great Three Days of Easter – as our liturgical enactment of a drama in three acts. Palm Sunday is the overture – setting up the major themes that will play out from Act I on Maundy Thursday through to Act III on Easter Day.

Of course, we know how the drama ends. But like a Shakespeare play – our knowing the ending does not deprive us of experiencing its spiritual impact in new and unexpected ways. Remember, it’s one thing to read the play in the comfort of an armchair, but it’s always a more meaningful experience to attend its enactment.

Crowds can communicate the exhilarating experience and act as conduits for a people’s collective memory. As Americans we find both a storyline of revolution and liberation alongside a darker storyline of civil war. Both storylines vie and clash in our collective memory – and in the present time we remain uncertain which storyline will find a conduit in the action of crowds.

Crowds are fickle because they evoke competing storylines.

Richard Lischer in his 2014 article in Christian Century notes his South African friend Peter Storey who once remarked that “America is the only country where more Christians go to church on Mother’s Day than Good Friday.” It is a sobering thought. Those who skip Maundy Thursday and Good Friday only to show up on Easter Sunday are missing the essential truth of Easter – which is that the Messiah was born in a grave (Paul Tillich).

We too are the victims of competing storylines. For like the crowds praising Jesus as he entered the Holy City, we enthusiastically hail our next political savior until that is, he or she no longer is. We long to do the brave thing, until that is, the moment when we don’t.