May 29, 2022

Easter 7 Year C

Sunday of the Memorial Day Weekend

Click here for previous Sermon Posts

Weekly Prayer Recording

The Power of Remembering

The Reverend Mark R. Sutherland

Recording of the sermon:

Click here for previous Sermon Posts

Weekly Prayer Recording

Recording of the sermon:

A nation’s collective memory of war is a patchy thing. Some wars we like to remember – others we try to forget. Within the collective consciousness of a nation’s war memories there are conflicting lessons to be learned, and in the case of the repressed memories, relearned.

We continue to mourn events in Uvalde this past week. A sense of outrage has been further stoked this weekend by the juxtaposition of optics. On the one hand, elementary school age children talking of their need to have predetermined hiding places worked out in anticipation of being shot and white men drooling over weapons of battlefield destruction at the NRA conference – held not only in the same week, but in the same state as the Uvalde tragedy.

The Evangelist Matthew writing of Herod’s slaughter of Bethlehem’s newborn sons in the days following Jesus’ birth, quotes directly from the prophet Jeremiah, (31:15):

“A voice is heard in Ramah, mourning and great weeping, Rachel weeping for her children and refusing to be comforted, because they are no more.”

Generations of our children continue to be traumatized by the unpredictable risk of being slain in the course of an ordinary school day. When school shootings become almost as common as school plays.

‘When, Oh Lord, will enough be enough?

When legislators owe a debt of fealty to the NRA in return for lavish campaign funding – enough will never be enough – ensuring that nothing will get done to make our country a safer place for innocent bystanders – safe for children in school, worshippers at prayer, concert goers, and shoppers in the market.

When, Oh Lord, will enough be enough?

Today is the Sunday of the Memorial Day Weekend and remembering in our theme. The staff have been preoccupied with the enormous task of clearing the offices in preparation for a long overdue renovation. So, it has been more than a bit chaotic around here. One of the challenges we’ve been grappling with has been how to deal with the accumulation of archival material. It’s everywhere, whole filing cabinets full – the result of decades of shelving the problem by just ignoring it – cramming it into yet more filing draws or removing it to an even more chaotic document dump in a mildewing room under the Great Hall stage.

During my time as rector the debate has continued unresolved between the archeologist-minded and the pragmatists around not only what to save, but how much to save. Do you save everything, or do you make representative selections? I’m not an archeologist – and so I tend towards the pragmatists – some materials are emblematic of our history and must be preserved for posterity. Let me hasten to add that I’m not speaking of the parish’s official document records – registers, minute books, legal documents which are all in the walk-in safe. The question is – in the draws full of Sunday bulletins, past stewardship materials, and other yearly communication letters dating back decades – how much of this is necessary to save?

The argument will remain unresolved, I suspect. What’s slightly aggravating from the pragmatist angle is that among those who argue for the preservation of everything there is no one prepared to take on the archival task. Like so much else in contemporary parish life, we’re long on opinions of what to do, but short on actual hands prepared to do it!

A deeper reflection on our archival quandary goes to the heart of what it means to remember. How to preserve a continuity of memory begs the question of not just what and how to preserve memories, but what do memories teach us – what lessons are we to draw from memories?

The Memorial Day weekend betokens the promises of summer after the grueling experience of a New England winter. The three-day Memorial Day Weekend is a godsend for many of us, and so I trust that families and friends will find time for well needed recreation.

However, the Memorial Day Weekend evinces national memory – in particular, the memory of the fallen in war – the men and women who gave their lives for the defense of the nation.

In A Hobbit, A Wardrobe, and A Great War Joseph Laconte writing about the tenacity and courage of the ordinary British soldiers who endured the unspeakable horrors in the trenches of the Great War, comments:

Historians still debate the ultimate achievement of these soldiers, and the causes for which they fought. Were they merely fodder for a vast and merciless military machine that ravaged Europe to no good end? Or did they play a vital role in halting ….. aggression and preventing the dominance of a brutal and oppressive juggernaut over the Continent?

Laconte locates the origins of J.R.R. Tolkien’s vision for the Hobbits and the role they played in confronting evil in his seminal Lord of the Rings epic. Tolkien the soldier, lived among, and fought alongside very ordinary men plucked from the shires and towns of the British Isles. Laconte observes that the “small people” who fought and suffered in the Great War helped inspire the creation of the unlikely heroes in Tolkien’s greatest imaginative work.

A nation’s collective memory of war is a patchy thing. Some wars we like to remember – others we try to forget. Within the collective consciousness of a nation’s war memories there are conflicting lessons to be learned, and in the case of the repressed memories, relearned.

Laconte’s words are applicable to the men who made up the armies of America’s iconic war, the American Civil War – men plucked from the farms and towns of a nation barely 90 years old. It is said that there is no more brutal conflict than when fellow citizens – brothers, cousins, fathers, and uncles take up arms against one another. As the armies of the Civil War crossed and re-crossed each other in what must at the time have seemed an endless game of tug-of-war for territory and advantage, it was also the women, the children, and the old men who remained at home who bore the brunt of this savage conflict in which they endured the horrors of war in the hope for something better.

Flash forward to 2022 and Laconte’s words can be reapplied to Ukraine’s defense of their desire to exist. Ranged against them are once again the forces of sacred violence shaken well into a heady cocktail of Russian religious and imperialistic dreams. For this is a war that floods our 24/7 newsfeeds with the direct horror of war’s savagery when waged against unarmed civilians – the men, women, and children of countless Ukrainian villages and towns. Yet, despite the daily horrors of war, resistance to scared violence is mobilizing the collective will of ordinary people willing to bear the horrors of war in defense of their hope of a future better than their past. Ukrainian experience is not unique. Around the globe other peoples are facing the evils of oppressive governments or caught up in the endless cycles of communal and religiously stoked violence. Most significant from our American point of view is to note how the significance of Ukraine’s experience is not bings lost on Taiwanese and other SE Asian democracies. But Ukraine differs in this respect. This conflict represents an attempt to destroy the rules based world order – an order which even China is wary of upsetting, preferring instead simply a greater influence within it. It is already creating dire economic and food security consequences for countless millions across the globe. Our support for Ukraine represents our realization that we cannot successfully stand aside.

Memorial Day preserves our collective memory of war. Important as this is, more important is the question concerning the lessons to be drawn from such memories. 20+ years of low-level insurgency wars in the Middle East are the result of drawing the wrong lessons from our collective memory of war. To our cost the withdrawal from Afghanistan only cemented the realization that we should not have been there in the first place. Afghanistan is the resurfacing – the Deja Vue experience – of living through something we’ve lived through before. Vietnam, our war memory we’ve tried so hard to forget – and because we had convinced ourselves to forget, became Afghanistan.

Failure to remember is the most dangerous thing a nation can do with its collective memories of war – for what we fail to remember we are destined to endlessly repeat. But drawing the wrong conclusion from among the divergence of war memories is the other danger.

Despite some superficial appearances to the contrary, the Russian invasion of Ukraine is not 1914 again. It is not a European parochial entanglement we can afford to sit out. It’s 1939 again. It is a confrontation with a brutal and oppressive juggernaut in the hands of a regime that has no qualms in employing military power to maximum destructive effect. A regime inspired by the heady mix of religion and imperium – driven not only to subjugate its neighbors but heedless of the huge sacrifice exacted from its own population. A regime for whom enough will never be enough. We need to access the right memory if we are to avoid drawing the wrong lesson and heading off in the wrong direction.

In A Hobbit, A Wardrobe, And A Great War, Joseph Laconte uncovers the sources of the hugely imaginative writings of J.R.R. Tolkein and C.S Lewis. Both men enjoyed a strong friendship forged by their common experience in the First World War. Their friendship grew out of a mutual need to take the memory of the horror of their experience of war and sublimate it into imaginative works of fiction that hold in tension the horror of war with the hope for something better. Together, Tolkien and Lewis created a transgenerational rediscovery of faith, friendship, and heroism – qualities so much in need today.

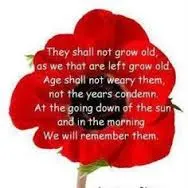

Before the memory of the fallen we must stand in silence:

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them. For the Fallen, Robert Laurence Binyon

Visit History.Com