August 20, 2023

Twelfth Sunday After Pentecost, Proper 15

Click here for previous Sermon Posts

Weekly Prayer Recording:

Click here for the Prayers of the People.

The Hardest Thing of All

The Reverend Mark Sutherland

Recording of the sermon:

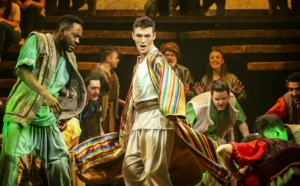

Image Jaymi Hensley in Joseph and his Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat

We have the advantage of psychological curiosity. For us the patriarchs are stories speaking to the enduring human nature of personal and family tensions.

The OT readings from both last week and today focus on Genesis’ story of Joseph.

Last week I offered a 30,000 ft overview of the book of Genesis – the first book of the both the Torah, and Christian Old Testaments. It’s part of what is known as the Deuteronomic corpus composed sometime between the 7th and 6th Centuries BCE. In a way we might think of the Deuteronomists as the equivalent of our Founding Fathers, whose writings laid out the constitutional framework for the new nation emerging after victory in the Revolutionary War. Similarly, Deuteronomists wrote a history of Israel to cement the transition from a loose tribal confederation into a centralized monarchy through the central theological filter of Israel’s covenant with God.

The Deuteronomic history follows a pattern with Genesis accounting the stories of origins. The book of Deuteronomy retells the Exodus experience with the books of Joshua, Judges, focusing on the period after Israel’s conquest of the land. Samuel 1 and 2 and Kings 1 and 2 cover the period of political transition from tribal confederation to monarchy – and the period of the Monarchy under David and its eventual fragmentation after the death of Solomon. A major theme in the Deuteronomic history is the explanation of God’s punishment of Israel when it ignored God and the covenant. Thus it was later re edited into its final form by the priestly scribes seeking to explain the reasons for the Babylonian Exile.

As the the written synthesis of older oral stories predating by centuries the written text – Genesis comprises two great narrative sweeps. The first begins with the creation stories, detailing the fall, the flood, and other myths – stories from before the beginning of recorded history. The second narrative sweep in Genesis brings us into human history with the personal stories of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and Joseph. These story cycles are the result of a weaving of originally unrelated oral traditions into a family story of father, son, grandson, and great grandson. The Joseph story epic is truly a family saga in the vein of the recent HBO drama – Succession.

Who is Joseph? The short answer is he is Jacob’s next to youngest son – born to him in his old age by Rachel his first and most beloved of his four wives. Put politely, Joseph is something of a teenage brat, who plays on his father’s favoritism to really piss his older brothers off. To add insult to injury, as a sign of his favoritism Jacob weaves Joseph a coat of many colors – the inspiration for Tim Rice & Andrew Lloyd-Webber’s musical Joseph and His Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat. The sight of Joseph preening and prancing around in his coat – the reminder of Jacob’s favoritism – must have been a daily provocation to his brothers. As Rice & Lloyd-Webber’s title hints at Joseph was not only a prancer, but he was also a dreamer – more precisely the receiver and interpreter of what Carl Jung called big dreams.

To cut a long story short, consumed with jealousy, his brothers intending to murder him threw Joseph into a dry well. But after second thoughts they pulled him up to sell him to Midianite traders who in turn, sold him on into slavery in Egypt. Through a series of events Joseph’s gift for dream interpretation enables him to climb out of slavery and up Egypt’s political ladder. He eventually comes to the notice of the Pharaoh himself – as the one to interpret a very troubling dream Pharaoh had about seven fat cows who devour seven skinny ones. Joseph interpreted the cows as seven years of good harvest followed by seven years of famine. He so impressed Pharaoh that he made Joseph prime minister with responsibility for putting the dream’s interpretation into practice. Joseph confiscated seven years of good harvest and stored the grain away in barns to ensure survival during the seven years of famine. Egypt’s continued abundance of grain during the famine years compelled Jacob to send a delegation of his sons – all except the youngest Benjamin – down to Egypt to buy grain.

The brothers come before the Prime Minister as bedraggled supplicants. Of course, Joseph recognizes them, even though they have no idea he is their long lost brother. Joseph, the inveterate joker, plays on their ignorance – manipulating them into returning home with gifts for their father and a request to return with the youngest brother, Benjamin.

On their return, Joseph can’t keep the charade up any longer. He breaks down in front of them. Today’s reading opens on this scene when Joseph reveals himself to the extreme consternation of his brothers. He cries:

I am Joseph, is my father still alive? But his brothers could not answer him, so dismayed were they at his presence. And they came closer, and he said, I am Joseph, whom you sold into Egypt.

But instead of savoring the moment – revenge being a dish best served cold – seeing their distress Joseph allays their fears of retribution. He explains to them that God planned all this – sending him ahead so that he might be in position to save them from dying of famine. There is much weeping, kissing, and hugging – to the puzzlement of all in Pharaoh’s household.

With the Patriarch epics and esp. the Joseph story cycle – the Deuteronomic compilers objective was to construct an account of origins. With the Joseph saga the stage is set for the next installment in Israel’s history with Moses and the Exodus.

We have the advantage of psychological curiosity. For us the patriarchs are stories speaking to the enduring human nature of personal and family tensions. Looked at from this angle, the spiritual value of the Joseph story lies in its study of conflicting human emotions – favoritism, jealousy, rivalry and hatred, betrayal, revenge and the complexities of forgiveness.

Joseph – the visionary trickster – is not above playing with his brothers and making them squirm. But this is the extent of his desire for revenge. As a dreamer and interpreter of dreams, Joseph has always been able to penetrate the thin space between human perception and divine intimation. He’s had time to meditate with gratitude on God’s larger purpose for him – with the arrival of his brothers, this purpose is given ultimate meaning .

In today’s portion we see him abandoning his game-playing to reveal himself as someone who responds to memories of betrayal. He meets the impulse for revenge with forgiveness. The brothers are relieved and yet continue nevertheless to feel disquieted because they remain stuck in a more primal stage of emotional development in which one bad turn always deserves another. In Joseph’s self-revelation, they are confronted with having to process the hitherto unprocessed unconscious legacy of their jealousy and murderous intent toward their younger brother.

Today’s portion ends with a scene of tearful reconciliation. The youngest brother, Benjamin, has joined them in Egypt and their ancient father Jacob will soon do so. It seems all’s well that ends well. But emotions are never so simple.

With Jacob’s death in the final chapter of Genesis, at chapter 50:15 we read:

Realizing that their father was dead, Joseph’s brothers said, “What if Joseph still bears a grudge against us, and pays us back in full for the wrong that we did to him?”

Learning from experience seems not to have been a skill Joseph’s brothers had acquired. They once more concoct a lie to ward off what they imagine is Joseph’s desire for revenge – in reality their own projections of unresolved guilt. They tell Joseph that Jacob’s dying intention was to beg him to forgive his brothers.

Without the benefit of a modern psychological analysis, the 6th-century BCE Deuteronomists knew that it’s easier to forgive than to be forgiven – or more specifically, to forgive ourselves through the transformation of being forgiven.