July 4, 2021

Click here for previous Sermon Posts

Weekly Prayer Recording

Sermon audio from Linda+

SERMON

Telling the Full Story

2 Samuel 5: 1-5, 9-10

The Rev. Linda Mackie Griggs

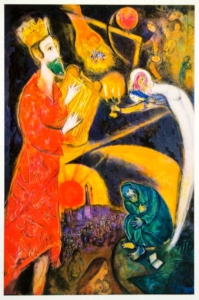

Feature picture: King David. Marc Chagall 1966

Biblical history, will teach us nothing without critique, truth-telling, and the resurrection of buried, silenced, voices. It is the narrators of the story who have the responsibility to make sure that we see the full picture in all of its challenging truth, and it is our responsibility not to look away.

“And David became greater and greater, for the Lord, the God of hosts, was with him.”

This entire passage in Second Samuel has a “happily ever after” sort of ring to it as the tribes of Israel ask David to be their king. He makes a covenant with them before the Lord and they anoint him. It seems like a happy ending; the more so because much of what we have heard over the past few Sundays has involved only a rough framework of David’s story, beginning with his earlier anointing by Samuel: A nobody eighth-born shepherd boy secretly made successor to Saul; David’s battle with Goliath; his rise to power and influence in Saul’s court and subsequent flight from Saul’s jealous rage; his love for Jonathan, and his heartfelt (and arguably unexpected) lament for Saul and Jonathan, both killed in battle with the Philistines.

And now David is King over all Israel, in fulfillment of God’s plan for him: “It is you who shall be shepherd of my people Israel, you who shall be ruler over Israel.”

You, David, You. Not Saul. Not anybody else.

Read this way, it all seems so cut-and-dried. But when we accept the narrator’s invitation to read between the lines and stray outside the boundaries of Sunday-only lectionary selections, we will see a fuller picture. As Mark noted last week, we have domesticated David, who is, “not only an inveterate womanizer –he is a very poor role model for emotional commitment and ethical fidelity as we understand these today. He’s a man of his time and place. A warrior king, abusive husband, and terrible father.”

But wait, there’s more! David’s path to power is anything but smooth, and the costs are high, though not for him. The more detailed story that we don’t hear on Sundays contains as many twists as a beach read by LeCarre or Ludlum. In brief, after David flees from Saul, Saul’s troops pursue him throughout the wilderness as David gathers supporters. Twice he has the opportunity to kill Saul, but he doesn’t; arguably because of his patience and trust in God’s promise (“You, David, you”); but also arguably because he’s smart enough to know that regicide isn’t always the best path to power. After Saul’s eventual ignominious death in battle, there is now a vacancy for a king. David is aware that he is God’s chosen, but he is also aware that he is not in direct line for the position. The next thing we know everyone who is in David’s way is either neutralized or dead, and those directly responsible for the assassinations are also dead. The elders of Israel look around and–Surprise!–there is only one candidate for king left standing. And David is innocent as a newborn lamb, his hands completely clean.

Old Testament scholars Carolyn Sharp and Walter Brueggemann both note the narrator’s use of irony throughout the story—“so all the people and all Israel understood that day that the king had no part in the killing…”—reading this we are invited into the conflict and nuance of these events; they should not be taken at face value. The narrator has observed the silencing of opposition to David, even as they note the importance of the fulfilling of God’s promise to David and to Israel. It is an uncomfortable space in which to be.

Brueggemann writes: “[T]he narrator wants to assert that David’s rise to power is marked by a deathliness that is costly for all parties, including David. David is indeed innocent, as the narrative claims, but he and his regime surely are not immune to the pervasiveness of death that is all around.”

Why bring this up? David was God’s choice to be king of all Israel. He brought greatness to Israel and to Jerusalem—the City of David. He was devoted to God and he was the shepherd of his people. Why spoil the narrative with irony and nuance and inconvenient shadow on this great king who did so much, and who really only made that one mistake with Bathsheba and Uriah, for which he repented and paid dearly (see 2 Samuel 11)? Why must we face the possibility that the mistake with Bathsheba and Uriah was just the one in which David got caught?

Why? Because without the critique and the irony and the nuance we don’t have the full story. And without the full story we are denied the richness of the learning that comes from it—from engaging the really difficult questions of privilege, power and ambition; the silencing of opposition; and where is God, really, in all this violence,;and can a shepherd be both good and bad at the same time?

Why bring this up? Because history, even Biblical history, will teach us nothing without critique, truth-telling, and the resurrection of buried, silenced, voices. It is the narrators of the story who have the responsibility to make sure that we see the full picture in all of its challenging truth, and it is our responsibility not to look away.

These questions of history and critique seem particularly poignant now, as we wrestle with the fraught issue of how to choose the lens—or lenses—through which to view our country’s past, especially in the light of our nationwide conversations and conflicts around racism, and also especially on this Sunday the 4th of July, at a relatively infrequent calendar intersection of the Lord’s Day and a civic holiday.

I have a fond memory: My husband (who has given permission for me to tell this story), every 4th of July, (until the kids lost interest,) used to read the Declaration of Independence—Every. Single. Word.—out loud from the Charlotte Observer, who printed it every year on the editorial page. It was a stirring reading, especially as he approached the end:

“We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.”

(We always loved that part.)

“And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.”

The cause was just. As with King David in Israel, there is much to celebrate today—a rich history, and much to be proud of. But those things which we rightly celebrate must be held in conversation with the shadows that tell the full story of who we are, what it has cost, and who has paid the price.

In July 1852 Frederick Douglass wrote: “The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought light and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.”

The voices that have been silenced and buried are crying out for resurrection. The critiques, the difficult conversations, need to take place. That is how we can ultimately be whole and healthy; by releasing denial of our wounds and making room for the uncomfortable healing truth.

As it so often does, it comes down to our identity as the household of God, and Baptismal Covenant:

“Will you seek and serve Christ in all persons, loving your neighbor as yourself?…Will you strive for justice and peace, and respect the dignity of every human being?”