November 28, 2021

Click here for previous Sermon Posts

Weekly Prayer Recording

Recording of the sermon

Live streaming of the November 28th Service

Sermon

First Steps

The Reverend Linda Mackie Griggs

Advent I Year C

Luke 21:25-36

Malcolm and I have kept a special tradition since before we were married; on New Year’s Day we go for a walk. Sometimes it’s a hike in the woods or up a mountain ridge; sometimes we saunter along a beach or just stroll through the neighborhood. We’ve done some kind of a New Year’s walk almost every year for over forty years, and when we don’t we miss it. It’s really important for us to mark the turn of the year with a reboot of sorts—cleaning out the cobwebs, starting over afresh, and hopefully restoring ourselves to a right perspective. The fresh air and being out in nature help to remind us who we are; that the world revolves, but not around us, which is really a relief. When you live your life like an airline passenger who thinks that it is only your hands gripping the armrest that keeps the plane in the air, it’s really crucial to be reminded that there is actually something greater in charge of things. Or, as you often hear me say, that God is God, and we are not.

Hence the importance of the New Year’s walk.

Today, this first Sunday in Advent, is the Church’s New Year’s Day—a turning over of the liturgical calendar page; a new color for the hangings and vestments, a new Gospel focus (this year it will be Luke.) We mark the changing season with the lighting of the Advent wreath. And with a walk.

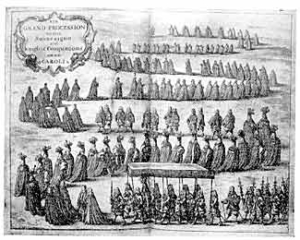

There was a time early in my spiritual journey when the three words, “The Great Litany”, would fill me with dread. The seemingly endless droning procession making what my son calls the Holy Pretzel through the church fell on my stony heart with a thud at best, and at worst reminded me of a scene out of Monty Python and the Holy Grail (NOT good if one is a member of the choir in the procession.)

Fortunately, with the passage of time and a deeper experience of The Great Litany, and of litanies in general, I’ve come around. Whether walking or kneeling or standing or sitting, this ancient form of prayer has become a welcome New Year tradition.

It hasn’t helped the Litany’s reputation that the secular use of the term “litany” has the negative connotation of being a long repetitive list of grievances, usually recited at you, wielded like a ruler on your knuckles. Actually the original meaning of the term in Greek was simply, “prayer,” and the tradition of litanies and processions dates back to fifth century Rome. In 1544 Archbishop Thomas Cranmer compiled and published the Litany for use in the churches, whereupon it became the first officially sanctioned liturgy in English, later included in the 1549 Book of Common Prayer. There have been a number of variations and permutations of the Litany over the centuries, including, thank goodness, the choice to omit the petition for deliverance from “the tyranny of the bishop of Rome and all his detestable enormities.” The 1979 Prayer Book includes the most recent form that we now know as The Great Litany, to distinguish it from others, including the Litany of Penitence, a Litany at the Time of Death, the Litany of Thanksgiving, and a Litany for the Nation. But the basic structure through them all is simply prayer and response. Prayer and response. So this is the most basic thing to understand about the Litany: We don’t do it, we pray it. As we literally or figuratively walk the Litany we walk our prayer, and as we do, we remember who we are and whose we are.

We begin by acknowledging the mercy and grace of the Trinitarian God who loved us into being.

O holy, blessed, and glorious Trinity, one God, have mercy on us.

We then turn, perhaps reluctantly, toward our shadow.

Spare us, good Lord.

Good Lord, deliver us.

This is our confession. Deliver us Holy One, from sin and sinfulness, from going astray, from things that can hurt us and others; Deliver us from things that we fear, or that we don’t like to admit we are capable of. In these petitions we speak of the unspeakable—our fear of death, pain, cruelty, injustice, and the violent and unexpected unknown. As we articulate these things, we envision them, these shadows. And with God’s help and deliverance we hope to discover that we can face them. That’s how confession cleanses and renews us—by inviting and challenging us to name and to face what we fear and what causes us shame. As a wise man named Mr. Rogers said, “Anything that is human is mentionable. And anything that is mentionable is manageable. “

In the mystery of thy holy Incarnation; by thy holy Nativity and submission to the Law; by thy Baptism, Fasting, and Temptation, Good Lord, deliver us.

Our praying now reminds us that our faith is rooted and grounded in Incarnation. God With Us, Emanuel; the Christ who was born into our complex human condition; who suffered, died, rose, ascended and sent the Holy Spirit to comfort and teach us. In this prayer we remember whose we are—that we are Christ’s own forever.

We beseech thee to hear us, good Lord.

Our Litany response now changes from deliverance to holy listening as we remember who we are: Bishops and presidents, prisoners and those in danger, searchers and laborers; the lonely, the broken, and the sick; the questioning and the doubtful. We pray that it may please God to bless and keep all of us—all connected whether we know it or not, whether we like it or not. We beseech the Holy One to hear us. Hear our cries and our whispers, our questions and even our accusations,; our songs and our praises.

O Christ, hear us.

Have you noticed the pronouns? This is not a first person singular prayer. Though we may each feel the impact of the prayer individually, it is the collective nature of the Litany that gives it its power—the power of the community to face the challenge and invitation of this moment in the knowledge that God is delivering us, hearing us,

calling us into hopeful faithfulness, together. This is how we face the birth pangs of the coming Reign of God that Jesus speaks of in today’s Gospel.

How might praying the Litany affect our Advent expectations? It is certainly countercultural, thanks be to God. Have you seen the headlines, “Will Supply Chain Issues Ruin Christmas?” Seriously? Can you imagine us chanting, “ “That it may please thee to loosen the supply chains for the movement of commerce so that we may have a bountiful Christmas, we beseech thee to hear us, good Lord”?

[Oh, Good Lord.]

Culture tells us it’s all about the presents. Advent calls us to be present to God. Culture tells us to accelerate and turn up the volume, while Advent challenges us to slow down and invites us into quiet. Culture tells us to worry, while Advent calls us into hopeful waiting—“...stand up and raise your heads, because your redemption is drawing near.” Culture tells us to check our cell phones, while Jesus calls us to look at the fig tree. Be alert! Look for the signs–the Kingdom of God is within reach!

Let us pray:

That it may please thee, O Lord, to keep us from despair at the world’s brokenness and to awaken us to hope. That it may please thee to fill our hearts with yearning for the coming of Christ. That it may please thee to inspire us to walk in love, ever alert for your presence among us and within us this Advent Season.

We beseech thee to hear us, good Lord.