September 5, 2021

Click here for previous Sermon Posts

Weekly Prayer Recording

Sermon audio from September 5, 2021

SERMON

Vocation

The Reverend Linda Mackie Griggs

Do you remember the first time someone asked what you wanted to be when you grew up? I was about four, and I said I wanted to be a horse. I was a little hurt when everyone laughed.

“What do you want to be when you grow up?”

It’s actually not as simple a question as it seems. For the small child it’s an invitation to dream; anything is possible—astronaut, opera singer, builder, writer. (Horse…) For the teen or young adult there is pressure: How do I choose what to do? Will I be able to support myself? Am I good enough to follow my dream? For the person at middle age it’s a different kind of pressure: What have I done with my life until now? Have I made a difference? Is it too late to dream?

On this Labor Day weekend we think of work. But in the context of our faith, work isn’t just about punching the clock. Work is something that takes up most of the waking energy of our lives, and for our lives to flourish work needs to be meaningful and balanced. So yes, work IS about dreams. Our dreams, and God’s dream for us: What is my calling, my vocation? What are my gifts? What sets me on fire? What won’t let me go–what is it that I can’t NOT do? In the words of Frederick Buechner, where does my greatest joy meet the world’s deepest need?

If there isn’t one already, there should be a theology of Labor Day. It would be based on the concept of the Imago Dei—the way in which our identity is rooted in the image of God. We have been created in the image and likeness of God, which means two things: As creatures made in God’s image we all carry the spark of the Divine within us that irrevocably connects us to God. And to be made in the likeness of the One whose spark we carry is to be creative beings; to live faithfully, persistently, and courageously into God’s call, however that manifests itself through our life and work. On Labor Day we may ponder how our work, and how the institutions and systems in which we work, reflect the Imago Dei—our calling to live into what we have been created to do and be. But no surprise here; our systems and institutions have a long way to go in embodying any kind of Labor Day theology.

This gap between the world as it is and the world we yearn for is an old story, and the writer of the Letter of James knew it well. First a bit of background: Scholars have concluded mostly through linguistic clues that the Epistle was probably not written by James, the brother of Jesus, as was claimed initially. Pseudonymous letters like this were common in the early centuries of the Church; probably tributes to those who were greatly respected in the community, like the Apostle Paul for example, or in this case, James, the leader of the Church at Jerusalem, who was revered as a wise, courageous shepherd and martyr for the faith.

So, the writer of the Letter of James—hereafter referred to as James—had strong opinions regarding economic justice and the importance of living one’s faith with integrity. His views on faith versus works, argued since the Reformation as a either/or binary, are actually a both/and argument for what we might call praying with your feet, or walking the talk: “Faith by itself, if it has no works, is dead.”

So how should the people of God manifest their faith through their actions? For James, the foundation of a life of faith and life in a faithful community lay in abiding by what he called God’s law of liberty, as given in the Commandments and especially as summarized by Jesus as “You shall love your neighbor as yourself.” For James the transgression of part of the Law was tantamount to transgression upon the whole of it, no excuses.

So, for James, to show partiality was as consequential a sin as murder and adultery—that’s how seriously he took it. In James’ theology, God’s heart was particularly open to the poor and disadvantaged. For James, the Beloved Community was a reflection of God’s care and compassion for the most vulnerable, and when the people of the community turned their back on that reflection by showing preference for their rich and powerful patrons with their gold rings and fine clothes, they were denying the very humanity of people who had been made in the image and likeness of God. They had committed a betrayal as grievous as adultery or murder. The way of the world was to give honor and privilege to wealth, power and outward appearance. The way of God—the Way of Jesus, on the other hand—was to throw the world’s rules out the window.

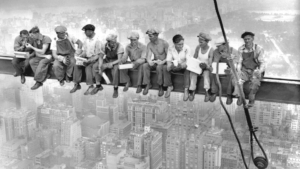

How to hold this passage in conversation with a Labor Day theology? Labor Day itself came about in the late 19th century in order to honor American workers as part of a labor movement which sought to redress the abuses of workers–the vulnerable– by industry owners and management—figuratively wearing fine clothes and gold rings– at the height of the industrial revolution; abuses such as low wages, unsafe working conditions, exploitation of children, immigrants and the poor. The way of the world was to privilege those with power and money while the most vulnerable suffered. For the workers in those days it was not a time for choices or dreams. Labor Day, and the labor movement that birthed it, celebrated the value of work for the individual, the family and the community. It celebrated the prospect of being able to dream beyond subsistence to

But it is not a perfect world, and I suspect James would still have plenty to say today about the vast wealth gap, the shrinking middle class, and the new Gilded Age.

“Is it not the rich who oppress you? Is it not they who drag you into court? Is it not they who blaspheme the excellent name that was invoked over you?”

The privileged of today are not always as obvious as the finely dressed and bejeweled patrons of James’ day. They may not even think of themselves as privileged. For example, during the pandemic many of us had the flexibility to work at home while others on the front lines were forced to risk illness or face losing their jobs. We see medical personnel in hospitals facing overwhelming emotional and physical workloads with the sick and dying, even as people refuse to take common sense measures for the well-being of themselves and their community.

“If a brother or sister is burnt out and exhausted, and one of us says, ‘Go in peace, you’re a hero’, but refuses to wear a mask or get a vaccine, what is the good of that?”

People work multiple jobs just to make ends meet. College graduates face outrageous student loan debt. Teachers pay for school supplies out of their own pockets, while the gap between CEO and employee pay gets bigger, and bigger, and bigger.

“My brothers and sisters, we demand same day delivery from Amazon, and we say to Jeff Bezos, ‘no, sir, you don’t have to pay federal taxes on your profits’, but to the delivery person we say, ‘keep driving, you don’t have time for a break,’ have we not made distinctions among ourselves, and become judges with evil thoughts?”

The institutions and systems that are the way of the world do not easily allow for dreams. They are crushing them.

But. The Wall Street Journal reports that workers are actually seeing increases in wages as companies offer incentives to attract workers in the post-pandemic labor shortage. They are able to seek jobs that pay better, even to look for work that is more interesting, fulfilling and less soul-sucking. To be able to consider vocation and not merely subsistence.

Some call it The Great Resignation, or the “I Quit” phenomenon. In another article (I did a lot of reading this week) called, “The Pandemic Revealed How Much We Hate Our Jobs. Now We Have the Chance to Reinvent Work”, Joanne Lippman writes of Kari and Britt Altizer, a Virginia couple who gave up their office jobs to run their own landscaping business. They have rethought their work, their time, child care, their commute—everything. They are able to dream again. “We’re not robots,” Kari says.

No, we’re not. We’re made in God’s image and likeness—to create, to flourish. To dream, and to be part of God’s Dream for Creation. As people of faith we are called not merely to desire and pray for those systemic changes that make meaningful work a reality for all of God’s beloved, but to agitate for them: to press for living wages, adequate health and child care, affordable housing, reduction of student loan debt. It’s all connected, just as we are all connected. No one can truly flourish until all of us have the opportunity to flourish; to match our greatest joy with the world’s deepest need.

As a society, as a Beloved Community, we are still in our infancy—we have a long way to go. But we are still forming and we have choices to make as we face our uncertain future.

What do we want to be when we grow up?