August 21, 2022

Eleventh Sunday After Pentecost

Click here for previous Sermon Posts

Weekly Prayer Recording

Unbinding

Sermon reflections from the Rector

Recording of the sermon:

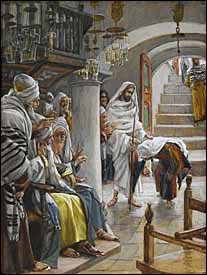

Image: Tissot – The woman with an infirmity of 18 year

Teaser:

In religious tradition and institutions, evil is to be found in the hardening of the human heart which privileges the protection of human power – a universal tendency to resist the continual reshaping by the demands of divine justice and mercy. If there is a judgment to be borne, then it’s that we are all found wanting when faced with the judgement of God’s justice and mercy.

Revisiting the story of the healing of the woman bent double from Luke 13 triggered memory for me. In an episode of the iconic series The West Wing, now alas, a faint whisper from a long-gone age, the issue of capital punishment is explored in the context of a request for a Presidential pardon for a man waiting on death row. Toby Ziegler, who is White House head of communications questions his Rabbi after Shabbat Service during which the Rabbi stated that vengeance is un-Jewish. Toby counters citing the Torah’s prescription of the death penalty for countless offences and infringements of the religious code.

The Rabbi replies that the Torah represented the best teaching in an historical context that saw the death penalty as the ultimate expression of reparation, i.e., sacrifice to God. He goes on to remind Toby of how over the following centuries the Rabbi’s in their commentaries on the Torah texts go to great lengths to confine and restrict the application of the death penalty by redefining reparation in ways that avoided the execution of the offender. Vengeance became un-Jewish – resulting from a deepening – a gradual evolution in Jewish understanding of divine justice.

In Luke 13:10-17 Jesus performs a healing on the Sabbath provoking a hostile response from the synagogue leader who objects to this as an infringement of the Sabbath work prohibition.

Luke 13:10-7 presents an example of Jesus’ embrace of nonviolent protest – in this instance against a religious tradition that is not evolving towards a deeper understanding of divine justice and mercy but rather the opposite – an interpretation of the tradition reflective of a hardening of the human heart. History reveals that if unchallenged religion – designed to be a conduit for divine grace – will inevitably degrade into an instrument for prevailing human interests – the business as usual of worldly oppression and discrimination.

For modern ears it’s easy to hear this episode as just another example of Jesus’ miraculous ability to heal sickness. Luke describes a woman seriously crippled. Yet, crippled is a rather smooth English rendering of Luke’s Greek synkypto – bent together– as in doubled over. She appears to be suffering from a form of spondylitis known as Marie-Strümpell Disease.

Noticing her, Jesus stops proceedings and addresses her saying you are released from your weakness. Placing his hand on her, she immediately straightens and gives glory to God causing the leader of the synagogue to accuse Jesus of breaking the Law of Moses by performing an act of work on the Sabbath.

Jesus accuses the religious leadership of hypocrisy. Citing the Sabbath exception to feed and water livestock – he argues that if this is allowed out of necessity then:

… ought not this woman, a daughter of Abraham who Satan bound for 18 long years, be set free from this bondage on the Sabbath day?

For Jesus, the hypocrisy lies in the use religious tradition to imprison and not to liberate – a use of tradition to mask the hardness of the human heart.

The gist of this encounter centers on Jesus’ recognition of the woman’s ailment as satanic binding. According to Jewish understanding of the time illness was either a punishment for sin – illness as moral judgement, or the result of satanic influences – illness as possession. What is significant in this encounter is Jesus’ prompt diagnosis of satanic influence.

This is no ordinary healing – if there is ever such a thing in Jesus’ ministry. His intention here is not to alleviate the woman’s physical suffering but to free her from bondage – an action he proclaims as particularly appropriate on the Sabbath as an action that give glory to God.

From Episcopal pulpits it is unusual – at least these days -to hear mention of Satan and satanic influences. So let me say a little to redress this deficiency.

In The book of Revelation, chapter 12 we read:

Then war broke out in heaven. Michael and his angels fought against the dragon, and the dragon and his angels fought back. But he was not strong enough, and they lost their place in heaven. The great dragon was hurled down—that ancient serpent called the devil, or Satan, who leads the whole world astray. He was hurled to the earth, and his angels with him.

This passage has fed the gnostic heresy that pictures humanity caught in an epic struggle between good and evil– between God and the Devil. Today this ancient heresy is very much alive and kicking in conservative and nationalist Christian circles. According to this worldview, any misstep on our part runs the risk of tilting the balance between the competing forces of good and evil. The mechanistic imperative to save souls is the only way to tilt the balance back in God’s favor.

Such a viewpoint is a profound denial of the victory of God through the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. It is a willful turning away from the power of the Easter story of victory and hope in favor of an ancient Middle-eastern story of the unending struggle between good and evil – which is neither Jewish or Christian.

That this heresy of cosmic battle between good and evil, between God and the devil is embraced among conspiracy minded Christians should come as no surprise. However, the imagery of Revelation is clear. Lucifer-Satan is defeated. His fall to earth is a metaphor for evil as something to be found only on earth – rooted in the human heart and enshrined in social systems of control and oppression.

The French philosopher, Rene Girard, states it neatly -Satan exists, [only] because we exist. By this he means that evil is an anthropological – a human, cultural construction, not a cosmic rival to the victory of God.

In religious tradition and institutions, evil is to be found in the hardening of the human heart which privileges the protection of human power – a universal tendency to resist the continual reshaping by the demands of divine justice and mercy. If there is a judgment to be borne, then it’s that we are all found wanting when faced with the judgement of God’s justice and mercy.

Here, we come back to heart of the matter in Luke 13: 10-17 where we find in Jesus’ confrontation with the synagogue leadership a foretaste of a later rabbinic tradition that came to understand that it is compassion and mercy not vengeance that lies at the heart of divine justice.