November 27, 2022

Advent 1

Click here for previous Sermon Posts

Weekly Prayer Recording

Come, Let Us Walk

The Reverend Linda Mackie Griggs

Recording of the sermon:

Full disclosure, this sermon may sound a lot like last year’s Advent I sermon, and that’s because it is a lot like last year’s Advent I sermon. But part of the richness of the cycle of the church year–with its daily round of prayer, weekly cycle of worship, seasonal movement through the major feasts of Christmas, Easter, Pentecost, All Saints, then back again to Christmas–the beauty of this cycle is that we hear the same themes each year, but always within a different context. The Gospel lessons are different–this year we move from Luke to Matthew. The world is different. Our lives are different. But God’s love and grace remain the same now and throughout time. Our Christian hope in God’s Dream for Creation remains the unalterable foundation for our faith.

So, new day, same story; and thus, we enter a new year for the Church.

Last year I began by talking about our New Year’s tradition of taking a walk at the turn of the calendar year, and how it helps us to reboot and refocus. What a delightful surprise to find that the first scripture of this new Church year ends with Isaiah’s words:

O house of Jacob, come, let us walk in the light of the Lord!

Isaiah was writing in the context of the siege of Jerusalem by the kingdoms of Aram and Israel during the Syro-Ephramitic war of the 8th c BCE. Isaiah’s prophecy was an assurance to King Ahaz of Judah that all would be well; offering a vision of hope and promise that God’s reign would ultimately be established for all of humankind. God’s reign would be twofold: judgment of idolatrous and unjust powers, as well as the establishment of God’s dream of community and peace instead of conflict and war.

“…they shall beat their swords into ploughshares, and their spears into pruning-hooks…”

This dream would require realignment of humankind’s priorities toward God’s priorities of justice and compassion. Isaiah articulated this as walking in God’s ways, or walking in the light of the Lord. He speaks of taking a metaphorical walk to help realign and reorient ourselves. So, we, on this first Sunday of Advent and of the new liturgical year, take a literal walk, praying the Great Litany.

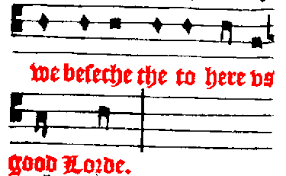

The original meaning of the word, “Litany” in Greek was simply, “prayer,” and the tradition of litanies and processions dates back to fifth century Rome. In 1544 Archbishop Thomas Cranmer compiled and published the Litany for use in the churches, whereupon it became the first officially sanctioned liturgy in English, later included in the 1549 Book of Common Prayer.

There have been a number of variations and permutations of the Litany over the centuries, including, thank goodness, the choice to omit the petition for deliverance from “the tyranny of the bishop of Rome and all his detestable enormities.” The 1979 Prayer Book (forty-four years old and still we call it “new”,) includes the most recent form that we now know as The Great Litany, which is distinguished from others, such as the Litany of Penitence, a Litany at the Time of Death, the Litany of Thanksgiving, and a Litany for the Nation. The basic structure for all of them is simply prayer and response.

Prayer and response.

So, this is the most basic thing to understand about the Litany: We don’t do it, we pray it.

As we literally or figuratively walk the Litany we walk our prayer, and as we do,

we remember who we are and whose we are.

Spare us, good Lord. We begin by acknowledging the mercy and grace of the Trinitarian God who loved us into being.

O holy, blessed, and glorious Trinity, one God, have mercy on us.We then turn, perhaps reluctantly, toward our shadow.

Good Lord, deliver us.

This is our confession. Deliver us Holy One, from sin and sinfulness, from going astray,

from things that can hurt us and others. Deliver us from things that we fear, or that we don’t like to admit we are capable of. In these petitions we speak of the unspeakable—

our fear of death, pain, cruelty, injustice, and the violent and unexpected unknown;

especially poignant this year in the wake of recent losses of our fellow children of God:

College students in Virginia and Idaho, queer folk and allies in Colorado Springs, and Thanksgiving shoppers, also in Virginia; all victims of senseless violence. As we articulate these losses and our society’s complicity in them, we envision these shadows within ourselves and society. And with God’s help and deliverance we hope to discover that we can face them. That’s how confession cleanses and renews us—by inviting and challenging us to name and to face what we fear and what causes us shame.

Good Lord, deliver us.

And then we continue: In the mystery of thy holy Incarnation; by thy holy Nativity and submission to the Law; by thy Baptism, Fasting, and Temptation, Good Lord, deliver us.

Our praying now reminds us that that our faith is rooted and grounded in Incarnation.

God With Us, Emanuel; the Christ who was born into our complex human condition;

who suffered, died, rose, ascended and sent the Holy Spirit to comfort and teach us.

In this prayer we remember whose we are—that we are Christ’s own forever.

The response changes again:

We beseech thee to hear us, good Lord.

Our Litany prayer now moves us from deliverance to holy listening as we remember who we are: Bishops and presidents, prisoners and those in danger, searchers and laborers; the lonely, the broken, and the sick; the questioning and the doubtful. We pray that it may please God to bless and keep all of us—all connected whether we know it not, whether we like it or not. We beseech the Holy One to hear us. To hear our cries and our whispers,

our questions and even our accusations; our songs and our praises.

O Christ, hear us.

Have you noticed the pronouns? This is not a first-person singular prayer.

Though we may feel the impact of the prayer individually, it is the collective nature of the Litany that gives it its power—the power of the community to face the challenge and invitation of this moment in the knowledge that God is delivering us, hearing us, calling us into hopeful faithfulness, together. This is how we wait, and keep awake, for the long awaited yet unexpected coming of the Son of Man that Jesus speaks of in today’s Gospel.

How might praying the Litany affect our Advent expectations? It is certainly countercultural, thanks be to God for that.Culture tells us it’s all about the presents. Advent calls us to be present to God. Culture tells us to accelerate and turn up the volume, while Advent challenges us to slow down and invites us into quiet.

Culture tells us to worry, and granted there is plenty to worry about, but Advent calls us into hopeful waiting. As Paul writes:

For salvation is nearer to us now than when we became believers; the night is far gone, the day is near. Let us then lay aside the works of darkness and put on the armor of light.

Let us pray:

That it may please thee, O Lord,

to keep us from despair at the world’s brokenness and to awaken us to hope.

That it may please thee to fill our hearts with yearning for the coming of Christ.

That it may please thee to inspire us to walk in love,

ever alert for your presence among us and within us this Advent Season.

We beseech thee to hear us, good Lord.