October 10, 2021

Click here for previous Sermon Posts

Weekly Prayer Recording

Sermon audio from October 10, 2021

SERMON

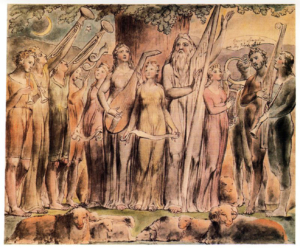

Liminal Times: Job a Meditation

The Rev. Mark R. Sutherland

Teaser

How do we proceed when between an ending and a new beginning—when the old way of doing things no longer works but a way forward is not yet clear?

At St Martin’s, we find ourselves between the joyful celebration of the success of Opening Our Doors to the Future – the capital campaign and the launch of our Annual Stewardship Drive for 2022. The capital campaign – beyond dollar amounts raised – is an expression of confidence from our current members in the future of St Martin’s. Next week, we will officially launch the stewardship drive for 2022. Over the course of its five-week duration, we will be asking our membership to review and renew their estimate of giving so that we can effectively plan for 2022, our 125th year.

However, this review and renewal process asks us to reflect on the question: can we let our imaginations become tools through which God’s dreaming for the world can flow more freely into our world?

We find ourselves in what Susan Beaumont in her insightful book How to lead when you don’t know where you are going –described as a liminal season. A liminal season is a shoulder season – a time in-between. How do we proceed when between an ending and a new beginning—when the old way of doing things no longer works but a way forward is not yet clear? It’s not only in the church but as a wider society we find ourselves in a liminal time when the continuity of tradition disintegrates and uncertainty about the future fuels doubt and chaos. In a liminal season it simply is not helpful to pretend we understand what needs to happen next. Prophetic words for us in this moment of history.

St Martin’s endeavors to occupy a place of tension weathering the uncertainty of the times through a commitment to traditional worship combined with a radical theological messaging that recognizes and attempts to speak into the uncertainty of the times. We are all watching the stalwart generation of faithful members pass on to the next great adventure and wonder who is coming up behind them to take their place? Our fear that we are on a trajectory of decline fills some of us with despair while provoking in others a manic attempt to delay what we all fear is inevitable.

In last week’s sermon I offered a sweeping overview of the essential themes found in the book of Job – a book that offers one of the most profound explorations of the nature of human suffering in the face of a God who often seems to us uninterested in our plight – a God who from our experience remains silent in the face of humanity’s age-old question concerning suffering – why?

In today’s Job portion we hear him exclaiming: Oh that I knew where I might find him, that I might come to his dwelling. We might read this sentence as Oh what I wouldn’t give to know that God is really there. Words that remind us of the partial nature of our knowledge and the narrowness of our vision.

Our vision is clouded with self-preoccupation and protests of self-importance – cutting us off from the divine energy for renewal. So much of our vision – both individually and in community is hedged-in by our need for reassurance. We strain to hear a false note of security – a grasping for knowledge as a defense against the uncertainties of the future.

Job continues:

I would lay my case before him, and fill my mouth with arguments, I would learn what he would answer me, and understand what he would say to me. Would he contend with me in the greatness of his power? No; but he would give heed to me. There an upright person could reason with him, and I should be acquitted forever by my judge.

Eventually, God will respond to Job in rhetorical metaphors that expose the human dilemma; we cannot know what we feel we need to know. We fill the vacuum in our knowledge with simplistic answers such as leading a charmed life is a sign of God’s favor and suffering means God’s punishment or abandonment. Feeling alone and abandoned in an indifferent universe – we cast ourselves even further adrift when concluding that because our suffering is not instantly alleviated – we are not given the miracle we demand, we cease to matter to God.

In the end, God responds to Job by effectively sidestepping his complaint. God will not meet Job’s complaint by justifying divine action or inaction. Instead, we will hear God reminding Job of the paradox of his quest for omniscience -to know the entirety of things:

Where were you when I laid the foundations of the world? Tell me if you have understanding who determined its measurements – surely you know! Who laid the cornerstone when the morning stars sang together, and all the heavenly beings shouted for joy?

We cannot know the entirety of things. We cannot know the future except in outline – glimpsed through a glass darkly. Yet, journeying into the future has never required us to know where we’re going. Oh, I know we like to pretend that we often do, but, we have never known the future before it arrives. In this lies grounds for hope. Instead of being preoccupied with our own construction of a future of either doom and gloom or of false and brittle certainties – can we let our imaginations become tools through which God’s dreaming for the world can flow with greater freedom? Our future lies in the mind of God and always has done!

If we learn anything from the serious practice of a spiritual life, God’s surprises are so much more exciting and fulfilling than anything – when left to the impoverishment of our own imaginations -we could predict or plan for ourselves.

Between the Job of the prologue and the Job of the epilogue lies the experience of his suffering. Job’s is not an experience of senseless suffering although through protest he demands for God to show him its meaning.

God never gives Job an answer to his insistent question why. Many see in this refusal to satisfy Job’s demand a suspicion that maybe God can’t give Job a satisfactory answer. Nevertheless, between beginning and ending lies the experience of change and being changed – albeit by something pretty awful. Maybe this is the purpose of Job’s suffering – a catalyst for change.

In the beginning, before Job has everything he cherishes taken from him, he believes that his prosperity reflects his own greatness. In this he is a great icon for many of today’s obscenely wealthy 1%-ters. The book ends with God’s restitution to Job not simply of the original wealth taken from him but of a magnification of that wealth tenfold. But Job is not the same man he was before. Suffering has changed him, and he now understands his wealth as a sign not of his greatness, but of God’s. His wealth is no longer his, but a sign of God’s generosity.

Job’s response to God’s generosity is gratitude. How might any of us express our gratitude? By a dedication and commitment to live in turn, with greater generosity.

Job now does something unheard of – as a sign of his gratitude for all he has he rewrites his will – settling portions of his estate on his three daughters as well as his male heirs. In the time in which this story is set, this action would have been unthinkable -beyond the capacity of the ancient imagination.

Can anything be a clearer demonstration of job as a changed man?

Living amidst the uncertainties, the fear, doubts, and violence of a liminal time, we might pay greater attention to our part in the unfolding of God’s dream for the world. The flow of God’s dreaming for the world requires only two things from us. The first is a capacity to be endlessly curious in the face of doubt and fear. And the second is a willingness to be changed in the direction of becoming more fit for God’s purpose!